Most people know you for your skateboard graphics, but I recently found out that you created the Toy Machine logo—one of my favorite of all time. Have you had a hand in many other logo designs?

Not that I can recall? Or at least nothing that great or memorable. To be honest, logo-design has always been my Achilles’ heel as an artist. Even with the Toy Machine logo, Ed had specifically asked me to do a simplified “3D” version of the earlier monster logo after he received a cease ‘n’ desist from the original artist. So I really just did the illustrative aspect; he added the type and away it went from there. I never imagined it would still be running strong over two decades later, though, not to mention innumerable tattoos across the world. Oh, here’s a random one, though: I did a few of the titles on early Big Brother magazine covers, like Issue 5, the cereal box “Sugar-Coated Penis Pops” logo for Issue 6, the “Hermano Grande” for Issue 11, and then the splattery one on Issue 12.

You mentioned doing storyboards for commercials a little while ago. What other work are you doing these days outside of skateboarding?

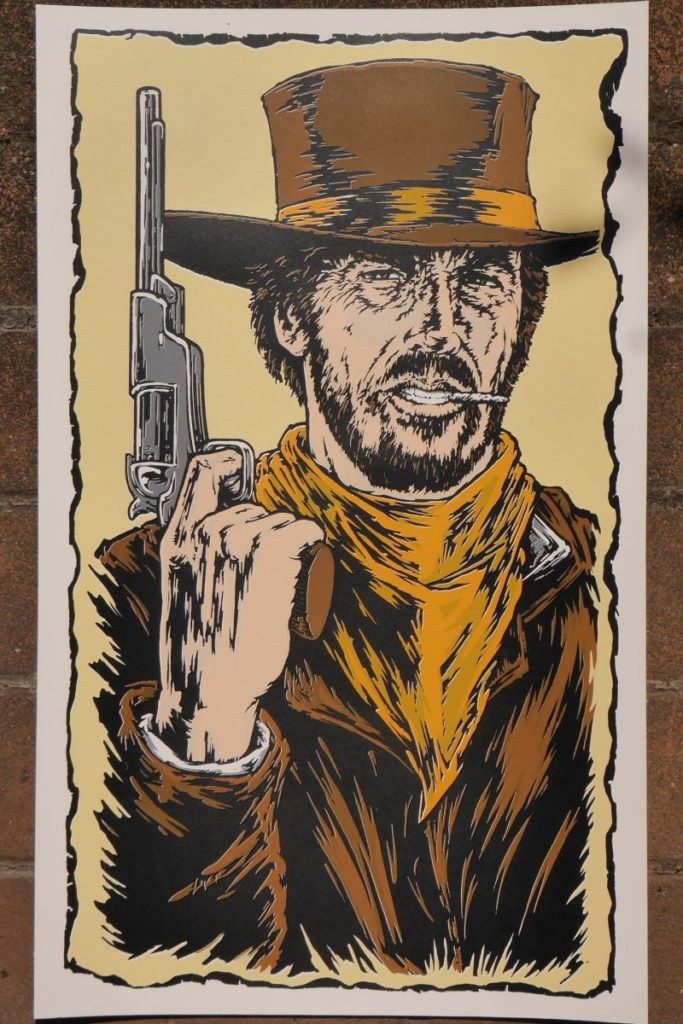

Yeah, every once in a while Jeff Tremaine will enlist me to do storyboards for various projects he’s hired to direct, like I did all the boards for the American Airlines safety video they play prior to take-off now, ridiculous as that sounds. Other than those art jobs, I’ve only ever picked up some random poster art gigs for Pearl Jam, Blink-182, and most recently the Pixies. I’m really not sure what I’m doing with my life.

You are largely accredited along with Marc McKee in shaping the narrative of skateboard graphics of the ‘90s. Who are some of your favorite contemporaries from that period, and from that era do you have any particular favorite graphics? Favorite graphic that you ever did for the World camp?

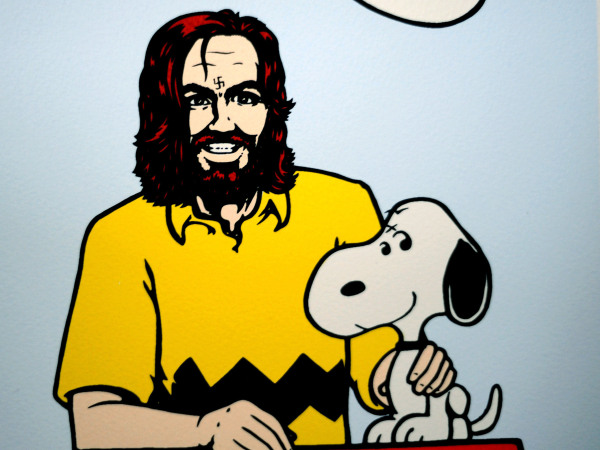

Well, thank you, but Marc McKee deserves about 95-percent of that narrative credit. I was just lucky to be working alongside him then. He set the bar and I did my best to try and keep up as he kept raising it higher and higher, especially with his slick bottom work circa 1992–1994 for World, 101, and Blind—the majority of which went largely unseen because the industry was in the shitter. Companies like to liberally throw around the “limited edition” word these days, but back then there was no such marketing thing and the boards were only produced in quantities of 200–300. So many good ideas for so few eyes. Anyway, back then, I always liked the Alien Workshop slicks by Mike Hill. And as far as my own personal favorites, there were a few on 101, like Eric Koston’s “Day at the Zoo” board, Adam McNatt’s “Charles Manson Brown,” and the Markovich Pushead/Zorlac spoof, and then of course the Chico Brenes “Nude Beach” board for World Industries.

Closeup of “Charles Manson Brown” graphic for Adam McNatt/101.

You recently started a company, Paisley Skates, along with Paul Urich, based in San Francisco. What was your main motivation for doing so?

On one hand, I was trying to add some stability to my anxiety-riddled life of freelance feast and famine; on the other, I was frustrated by the industry climate and trends, and how the “creative-fuck-all-outcast” elements of skateboarding had been superseded by the whole “business-sport-athlete” aspect. So I wanted to revive a bit of the finger-flipping freedom, along with the aesthetic desire to screen-print the graphics in the same manner they were back then—bottom line and budgets be damned. Needless to say, none of this has made for a lucrative business model, but it’s been a lot of fun and I’m really proud of everything we’ve somehow managed to produce. The best thing, however, is that Paisley has grown way beyond the original “art project” origins and “wall-hanger” perceptions to take on a legitimate life of its own, which is awesome because the last thing I wanted to make were skateboards that people didn’t actually skate.

The “Serial Killer” graphic you did seems to harken back to the World era graphics of the 90’s; was that something you recently completed or had been sitting on for awhile?

What’s funny is that I first conceived the graphic way back in 2003, but my son had just been born in 2002 and for whatever reason it made me feel weird in that way you never fully understand until you’re a parent. Maybe ten years later, though, I finally got around to doing a rough sketch. Even then a few companies passed on the idea, so it never found a home until we founded Paisley in 2015. The fact we were able to get the “Serial Party” screen-printed made it even better, although I think it may have given the printer a near nervous breakdown and he refused to print it ever again. So on subsequent runs of the board we had to get them screened down at Screaming Squeegees.

Your book Disposable: The Skateboard Bible is seen as the authoritative guide on skateboard collecting. Are you much of a collector yourself, or were you just interested in documenting the history of skateboard graphics? Any plans for new editions?

At one point in time I was very much an out-of-my-mind collector and managed to acquire a near complete line-up of original Powell-Peralta and Zorlac boards, but then life threw some curveballs—as life is known to do—and most all my collection had to be liquidated along with the personal archive of boards I’d done. But aside from all my OCD and nostalgia issues, yes, first and foremost there was the desire to document the history before it was forgotten or lost. Not to mention I was bothered, irritated, and embarrassed by most all of what had previously been published on the subject. Every once in a while I still get the itch to do another book, but I just haven’t found the time required to devote to such an undertaking—each of the previous books took two years to complete, making them very much of the passion project sort—and I just don’t have that luxury at present.

You’re primarily known as an artist, but have worn many hats including being the editor of Big Brother at one point in time. Do you enjoy writing or drawing more?

What I enjoyed most, I think, was the ability to bounce between the two, because it kept me from getting burnt out. Ideas, especially for board graphics, aren’t always easy to come by, at least for me, so the supplemental writing work probably prevented me from committing a gross number of tragedies throughout the ’90s—or at least way more than I did.

“Clint” prints that we did in 2015 (available here).

Do you have any good stories from the Powell days that nobody has heard?

Most all of them pertaining to graphics were written about in Disposable: A History of Skateboard Art, but I still have very distinct memories of the time in 1990 when Guy Mariano and Rudy Johnson quit the Bones Brigade to ride for Blind. I skated with them quite a bit back then, so it didn’t come as a total surprise when Gabriel Rodriguez called me up one night and said that they’d been hanging out with Mark Gonzales lately and that Rudy and Guy were going to quit. I went in to work the next day to let Todd Hastings know what was going on—he was the Powell team manager then—and he dismissed me, saying everything was fine, the guys were totally cool… but I knew better. The company was losing touch and that was the point when it really began to feel like the end of days for Powell.

You can buy Sean’s 101 Markovich print here.